Cybersecurity, AI, crime, fraud, risk, trust, privacy, gender, equity, public-interest technology

Pages

Wednesday, November 29, 2023

QR code abuse 2012-2023

Saturday, November 04, 2023

Artificial Intelligence is really just another vulnerable, hackable, information system

Every AI is an information system and every information system has fundamental vulnerabilities that make it susceptible to attack and abuse.

Criminology and Computing and AI

- a motivated offender,

- a suitable target, and

- the absence of a capable guardian.

Do AI fans even know this?

- Chips – Meltdown, Spectre, Rowhammer, Downfall

- Code – Firmware, OS, apps, viruses, worms, Trojans, logic bombs

- Data – Poisoning, micro and macro (e.g. LLMs and SEO poisoning)

- Connections – Remote access compromise, AITM attacks

- Electricity – Backhoe attack, malware e.g. BlackEnergy, Industroyer

As I see it, unless there is a sudden, global outbreak of moral rectitude, vulnerabilities in AI systems will—if they are not capably guarded—be exploited by motivated offenders.

|

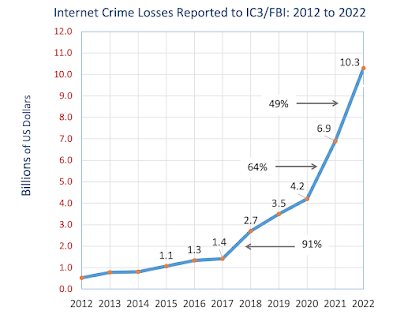

| Internet crime losses reported to IC3/FBI |

Wednesday, April 12, 2023

What is ChatGPT and how can AI get things wrong: an annotated example using jackware

|

| You can't trust what ChatGPT says |

The term "jackware" was coined by two researchers, Stefan Savage and Tadayoshi Kohno, in a 2016 paper titled "Experimental Security Analysis of a Modern Automobile". In the paper, Savage and Kohno described a proof-of-concept attack in which they were able to take control of a car's electronic systems using a laptop computer. They used the term "jackware" to describe a new class of malware that could be used to take control of vehicles in a similar way to how ransomware is used to take control of computer systems.

Frankly, at first glance this looks like is a very impressive answer: it names names and cites an academic source, while providing a helpful description of jackware, all articulated in grammatically correct English. It's way more helpful than the output of a plain old search. You can see why so many people get so excited about artificial intelligence.

But sadly, several key facts in ChatGPT's answer are just plain wrong, so wrong that you could be in serious trouble with your teacher-editor-readers if you pasted that paragraph of ChatGPT output into a piece of work. For a start, anyone familiar with the subject matter would know that you hadn't read that paper.

The academic paper to which ChaGPT refers was published in 2010, not 2016. You can see that from this listing of the paper. This is not just a pedantic quibble; the named paper is legendary in the world of automotive cybersecurity, partly because it was published way back in 2010. It documents groundbreaking work done by Savage et al. in the 2000s, way before the flashy Jeep hack of 2015 by Miller and Valasek.

More blatantly erroneous is the identification of this 2010 paper and its authors as the source of the term jackware. Simply put, the paper does not contain the word jackware. In fact, the person who coined the term jackware to describe malicious code used to take over vehicles, was me, Stephen Cobb, and I did that in May of 2016, on this blog, in a post titled: Jackware: coming soon to a car or truck near you?

In July of 2016, I penned Jackware: When connected cars meet ransomware for We Live Security, the award-winning global cybersecurity blog. As further evidence, I present exhibit A, which shows how you use can iterative time-constrained searches to help identify when something first appears. Constraining the search to the years 1998 to 2015, we see that no relevant mention of jackware was found prior to 2016: Apparently, jackware had been used as a collective noun for leather mugs, but there are no software-related search results before 2016. Next you can see that, when the search is expanded to include 2016, the We Live Security article tops the results:

Apparently, jackware had been used as a collective noun for leather mugs, but there are no software-related search results before 2016. Next you can see that, when the search is expanded to include 2016, the We Live Security article tops the results:

So how did ChatGPT get things so wrong? The simple answer is that ChatGPT doesn't know what it's talking about. What it does know is how to string relevant words and numbers together in a plausible way. Stefan Savage is definitely relevant to car hacking. The year 2016 is relevant because that's when jackware was coined. And the research paper that ChatGPT referenced does contain numerous instances of the word jack. Why? Because the researchers wisely tested their automotive computer hacks on cars that were on jack stands.

To be clear, ChatGPT is not programmed to use a range of tools to make sure it is giving you the right answer. For example, it didn't perform an iterative time-constrained online search like the one I did in order to find the first use of a new term.

Hopefully, this example will help people see what I think is a massive gap between the bold claims made for artificial intelligence and the plain fact that AI is not yet intelligent in a way that equates to human intelligence. That means you cannot rely on ChatGPT to give you the right answer to your questions.

So what happens if we do get to a point where people rely—wisely or not—on AI? That's when AI will be maliciously targeted and abused by criminals, just like every other computer system, something I have written about here.

Ironically, the vulnerability of AI to abuse can be both a comfort to those who fear AI will exterminate humans, and a nightmare for those who dream of a blissful future powered by AI. In my opinion, the outlook for AI, at least for the next few decades, is likely to be a continuation of the enthusiasm-disillusionment cycle, with more AI winters to come.

Note 1: For more on those AI dreams and fears, I should first point out that they are based on expectations that the capabilities of AI will evolve from their current level to a far more powerful technology referred to as Artificial General Intelligence or AGI. For perspective on this, I recommend listening to "Eugenics and the Promise of Utopia through Artificial General Intelligence" by two of my Twitter friends, @timnitGebru and @xriskology. This is a good introduction the relationship between AI development and a bundle of beliefs/ideals/ideas known as TESCREAL: Transhumanism, Extropianism, Singularitarianism, Cosmism, Rationalism, Effective Altruism, Longtermism.

Note 2: When I first saw Google take jackware to be a typo for Jaguar I laughed out loud because I was born and raised in Coventry, England, the birthplace of Jaguar cars. In 2019, when my mum, who lives in Coventry, turned 90, Chey and I moved back to Coventry, and that is where I am writing this. Two of my neighbours drive Jaguars and they are a common sight in this neighbourhood, not because it's a posh part of the city, but because a lot of folks around here work at Jaguar Land Rover and have company vehicles.

Tuesday, March 14, 2023

Internet crime surged in 2022: possibly causing as much as $160 billion in non-financial losses

This increase, which comes on top of a 64% surge from 2020 to 2021, has serious implications for companies and consumers who use the Internet, as well as for law enforcement and government.

Those implications are discussed in an article that I wrote over on LinkedIn in the hope that more people will pay attention to the increasingly dire state of Internet crime prevention and deterrence, and how that impacts people. In that article I also discuss the growing awareness that Internet crime creates even more harm than is reflected in the financial losses suffered by victims. There is mounting evidence—some of which I cite in the article—that the health and wellbeing of individuals hit by online fraud suffers considerably, even in cases of attempted fraud where no financial loss occurs.

One UK study estimated the value of this damage at the equivalent of more than $4,000 per victim. Consider what happens if we round down the number of cases reported in the IC3/FBI annual summary for 2020 to 800,000, then assume that number reflects a fifth of the actual number of cases in which financial loss occurred. That's 4 million cases. Now assume those cases were one tenth of the attempted online crimes and multiply that 40 million by the $4,000 average hit to health and wellbeing estimated by researchers. The result is $160 billion, and that's just for one year; a huge amount of harm to individuals and society.