I believe that the misuse and abuse of information and communications technology (ICT) threatens to undermine all present and future human endeavors, from raising children to reining in pandemics.

[Update May 14, 2020: a longer version of this article is now

available here, with narration. You can also find it

on YouTube.]

I find it helpful to think of this phenomenon as “the malware factor,” mainly because it is enabled by, and embodied in, malicious software, or malware. The following is an attempt to explain this point of view.

A pandemic example

In one of his less empirical moments, the English philosopher Francis Bacon wrote that "prosperity doth best discover vice, but adversity doth best discover virtue." Clearly, this was said before the invention of email and its subsequent perversion by morally-challenged humans bent on leveraging adversity at scale.

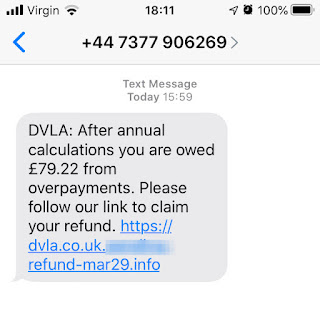

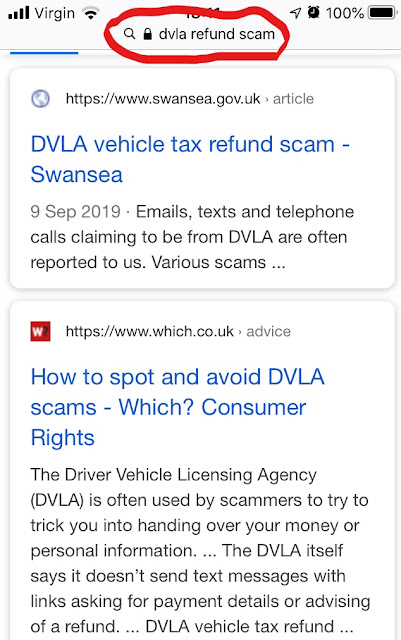

As any information security professional will tell you, when people are stressed by the struggle to cope with a crisis—a global pandemic, for example—they are more likely to click links that lead to scams. Of course, COVID-19 has led to many examples of virtue, but it has also sparked a global surge in digitally-enabled vice, a.ka. cybercrime, a.k.a crime.

(As I have said elsewhere, in a postdigital world, the term cybercrime is of limited utility. While we cannot say—yet—that all crime is cybercrime, just about all crime has cyber elements.)

Fortunately, some of the fine folks working to keep at bay the surge in digitally-enabled COVID-19 vice have been documenting the situation. By March 12, Alex Guirakhoo, research analyst at Digital Shadows had already catalogued a sickening array of technology abuse in a lengthy blog post titled

How cybercriminals are taking advantage of covid-19: scams, fraud, and misinformation.

Guirakhoo opens with an observation that has been true since at least September of 2001: "In the wake of large-scale global events, cybercriminals are among the first to attempt to sow discord, spread disinformation, and seek financial gain." He goes on to explain the implications of this twenty-first century reality:

"While COVID-19 itself presents a significant global security risk to individuals and organizations across the world, cybercriminal activity around this global pandemic can result in financial damage and promote dangerous guidance, ultimately putting additional strain on efforts to contain the virus."

While I might have said

immediately instead of

ultimately, Guirakhoo accurately framed the problem, one problem that is far more serious than most people realize, with implications very few have been willing to face—although I am hopeful that this is about to change.

Factoring in Malware

The current reality is that large-scale global events—as well as many regional and even personal human endeavors—are negatively impacted by unwanted human activity in cyberspace, activity that is enabled, at a fundamental level, by malicious code.

This is true of events or endeavors that take place in meatspace, or cyberspace, or both. For example, the physical distribution of medicine and equipment to contain a pandemic is negatively impacted, as is the strategy of having people use computers and the Internet to work from home to contain a pandemic.

Before digging deeper into the definition and role of malicious code in this current reality, let me address why I think it is helpful to refer to this reality as postdigital. These easiest way to do this is to quote Professor Gary Hall, Director of the

Centre for Postdigital Cultures at Coventry University:

the ‘digital’ can no longer be understood as a separate domain of culture. Today digital information processing is present in every aspect of our lives. This includes our global communication, entertainment, education, energy, banking, health, transport, manufacturing, food, and water-supply systems. Attention therefore needs to turn from the digital understood as a separate sphere, and toward the various overlapping processes and infrastructures that shape and organise the digital and that the digital helps to shape and organise in turn.

There is no need for me to restate what Hall says there; I agree that we need to acknowledge that "the digital" is now part of our lives and life on Earth, whether we like it or not (and to be clear, while "going off the grid" can minimize your interaction with the digital, it is still a part of your world—just check the night sky if you don't believe me).

Which brings me to these three assertions:

1. the misuse and abuse of information and communications technology (ICT) threatens to undermine all present and future human endeavor, from raising children to reining in pandemics; and,

2. it is helpful to refer to this as “the malware factor” because it is enabled by, and embodied in, malicious software, or malware, and embedded in the infrastructure of our postdigital world.

3. The use of malware by criminals and governments during the COVID-19 pandemic is prima facie evidence that our postdigital reality is based on code, abuse of which is impossible to prevent.

|

| Virus components in a human cell (BBC) |

I am going to end this piece right there, and leave it right here, with this coda: I'm not wedded to "The Malware Factor" as the name for this phenomenon, but before you discount it, please know that I have more to say on this, and it involves cells and viruses and infrastructure, and maybe a few passages from Genesis (the religious text, not the band).

In the meantime, it might be helpful to watch this BBC video:

Secret Universe: The Hidden Life of the Cell (warning: contains scenes of simulated violence between a virus and a human cell; may be geo-fenced, so here is an

alternative source and

also here).

And finally, here's a friendly reminder that, if Earth's leaders continue their pathetic track record on reining in malware, it will become a problem on Mars too. That's assuming humans make it to Mars safely, which I think is unlikely given the #MalwareFactor.

Note: If you found this article interesting and/or helpful, please consider clicking the button below to buy me a coffee and fuel more independent, vendor-neutral writing and research like this. Thanks!