This is the second part of an article in which I relate situational crime prevention to cybersecurity awareness (the first part is here, but this article also stands on its own, or at least I think it does).

The attitude that situational crime prevention or SCP takes toward crime is "worry less about the underlying motives of people who commit crime and focus on understanding the circumstances in which it occurs." Pursuing research with this focus, social scientists Felton and Cohen found that social, economic, and technological factors drive increases in the opportunities for crime; this led to the routine activity theory of crime which holds that:

crimes occur when there is ‘convergence in space and time of offenders, of suitable targets, and of the absence of effective guardians’ (Felson and Cohen, 1980)

From this perspective it is possible to develop techniques for curtailing the opportunities for crime, thereby producing a drop in crime. Over time, advocates of SCP developed this table of 25 techniques within five categories: increase the effort and the risks, reduce the rewards and provocations, and remove excuses (Cornish and Clarke, 2003).

Clearly, SCP has wide application in efforts to reduce crime in cyberspace as well as meatspace, starting with things as simple as choosing stronger passwords when establishing online accounts and using different passwords for different accounts. However, SCP can also help when cybercrimes get complex, for example when criminals use malicious code to illegally access millions of computers and organize them into botnets for nefarious purposes (including emptying online bank accounts even when they have strong passwords).

You can see how SCP helps to fight to cybercrime in this article by my friend Alexis Dorais-Joncas, Security Intelligence Team Lead at my former employer ESET, one of the world's largest security software companies: "Doing time for cybercrime: Law enforcement and malware research join forces to take down cybercriminals" is available on WeLiveSecurity. By focusing minds on the critical triad of "offenders, suitable targets, and the absence of effective guardians," SCP still has a serious role to play in crime reduction as well as security and risk management.

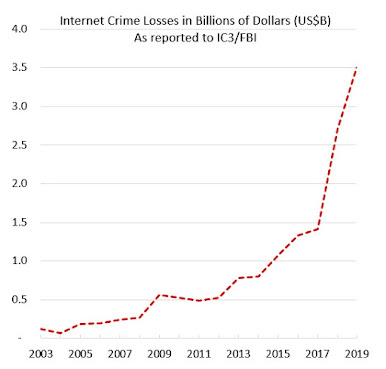

Unfortunately, as the chart on the right indicates, efforts to rein in internet crime do not appear to be succeeding. (For the reasons why this chart is a valid indicator, see my notes at the end of this article.)Of course, you could argue that not all of those efforts are wasted since we're still making extensive use of computers and the rise in crime losses is merely a reflection of our increased use of, and reliance upon, digital technology.

My response to that argument is four words: architecture, infrastructure, politics, and profits. The architecture of the spaces and places in which we live and work has, over the last 40 years, become less criminogenic, thanks to the influence of situational crime prevention. I don't think the same can be said of cyberspace. In fact, by the late 1980s it was clear to many technology experts that the fundamental building blocks of digital technology were riddled with holes, yet the world proceeded to build a massive global digital infrastructure out of those blocks.

Meanwhile, politicians failed to establish norms of behavior within cyberspace, partly because abuse of those blocks can generate funds and advantage, both of which are highly sought after in politics. And of course, the demand for cybersecurity products and services has created huge profits for some companies and minted numerous multi-millionaires and several billionaires. (Disclaimer: for a short period of time, that ended over a decade ago, I was a cybersecurity millionaire; these days I am nowhere near being any kind of millionaire, except maybe in Swedish krona.)

The opportunity structure for predatory crime

I started researching SCP to write a postgraduate essay on this topic: "The main problem with situational crime prevention is that it fails to address the root causes of crime. Critically discuss." I concluded that SCP does not even try to address the root causes of crime, but that is not its main problem. I argued that SCP cannot fully address the phenomenon of changes in society that produce new opportunities for crime at a faster rate than those opportunities can be reduced. This is the phenomenon that Felson and Cohen (1980:404) warned about in their early work on routine activity theory when they wrote: ‘opportunity for predatory crime appears to be enmeshed in the opportunity structure for legitimate activities’. Indeed, the phrase “opportunity structure for legitimate activities” is an apt description of the place where a massive and global crime wave is currently in progress: cyberspace.

Despite clear indications that the networking of computer systems greatly increases their potential for criminal abuse (Cobb, 1995), few calls for restraint in the adoption of network technologies have ever been heeded, at least on the basis of the criminal opportunities that they create. To give cybercrime some historical context, consider the 2013 attack in which 1,800 stores belonging to US retailer Target were penetrated. Thieves compromised 40 million payment card records, impacting over 100 million people (Star Tribune, 2014). By taking advantage of the opportunity that Target gave its suppliers to manage orders online, criminals earned around $54 million, based on the amount they were charging when they sold the stolen data in online markets; meanwhile, banks paid $200 million to replace compromised card (Krebs, 2014a).

To the best of my knowledge the perpetrators of the Target hack have never been brought to justice. The politicians who promised action to angry constituents who were victimized by the attack clearly haven't done enough to stem the tide of criminal technology abuse. This abuse generates profits at many levels, and in a rare win for law enforcement the Latvian computer programmer who designed "a program that helped hackers improve malware—including some used in the 2013 Target breach" was arrested, convicted and, in 2018, sentenced to 14 years in prison (Washington Post).

The fact is, the failure by governments to act effectively against cybercrime in the 1990s and 2000s led to the industrialization of technology abuse. Today, many cybercrime schemes employ proven business strategies such as division of labour, specialization, modularity, and marketing, including A/B testing. Furthermore, a large percentage of cybercrime is enabled by a sophisticated system of virtual markets that facilitate the buying, selling, and renting of cybercrime tools, resources, and stolen data (Krebs, 2014b, Ablon et al., 2014). This activity is often quite brazen, as I demonstrated to a radio journalist last year (recording here and backstory plus graphics here).

Cybercrimes are often executed by ad hoc groups of geographically dispersed individuals who have been developing virtualized trust mechanisms for at least ten years (Krebs, 2014b; Holt and Smirnova, 2010). A realistic assessment of the current state of affairs is provided by the Institute of Chartered Accountants (2014): ‘there is a growing gap between business and cyber attacker capabilities … Many businesses are falling further behind and the risks are growing’.

The problem is not that SCP has been silent on fighting cybercrime. IT security practitioners regularly employ technique number one in the table of SCP strategies: target hardening. The cybersecurity concept of “kill chains” has valuable parallels in “crime scripts” (Cornish, 1994, as cited in Clarke, 2012). Some criminologists were quick to apply SCP to cybercrime (Newman and Clarke, 2003). Unfortunately, the speed at which their recommendations have been outpaced reveals the nature of the problem: it is hard to “follow the money” when today’s cybercriminals prefer to take their profits in a crypto-currency like Bitcoin that did not exist in 2003 (Bradbury, 2013).

So I would argue that the main problem with situational crime prevention is its failure to acknowledge the following: just as crime prevention that is based on addressing the root causes of crime faces a daunting future because it requires fundamental changes in society, so too does any crime prevention approach based on reducing opportunities.I leave you with a slightly garish graphic that I made a few years ago, but which is probably still roughly correct, at least in terms of ratios (please DM me @zcobb if you have more recent numbers). The ratios between the spending figures tell me that the US government just does not grasp how badly wrong things could go if cybercrime prevention and reduction are not addressed with adequate resources. And while the US government does support cybersecurity awareness programs in October and throughout the year, there is way, way more work that needs to be done. The hockey stick of cybercrime needs to be turned into a downhill ski run towards a safer, brighter digital future.

#BeCyberSmart

Notes on my IC3 internet crime losses chart

While IC3 is the source of the numbers in the graph, IC3 has not—to my knowledge—published them in a graph, in other words, I built the graph from their numbers. The methodology behind the IC3 numbers shown in this chart is not likely to impress statisticians—an issue I covered in depth in this law journal article on crime metrics—the trend you see here is consistent with all the other measures of cybercrime that I have studied. Also note that the level of cybercrime has probably increased in 2020. Back in January, even before the "Covid Effect" kicked in—a huge surge in computer-enabled crime that began to emerge in late February—I predicted that the 2020 numbers from IC3 will blow past the $4 billion mark. Then, in early March we started seeing articles on "How cybercriminals are taking advantage of covid-19: scams, fraud, and misinformation." By mid-April, FBI Deputy Assistant Director Tonya Ugoretz was saying the number of crimes reported to IC3 had "quadrupled compared to months before the pandemic." Frankly, I hope I am wrong about the numbers for 2020 and would like nothing more than to see a drop in cybercrime. That does not seem likely to happen but you can bet I will blog about it if it does.

References for situational crime prevention

No comments:

Post a Comment