The "official" theme for week three of Cybersecurity Awareness Month, 2020, is Securing Internet-Connected Devices in Healthcare. This an important topic, but there are many aspects of cybersecurity as it relates to healthcare data and devices that need our awareness.

Let's start with this: medical information is fundamentally different from financial information. To understand what I mean, consider the consequences of the following actions as they relate to a person’s medical information:

- unauthorized access, change, disclosure, or destruction

- ransoming of access

- denial of access

All of those actions have the potential to create seriously negative impacts on someone's life, including ending it prematurely. Those same actions can definitely cause harm when directed at information that is financial in nature—like credit cards, bank accounts, online purchases—but not like the abuse of medical information.

This is not a fresh insight. Consider this true story which I cited in my 1995 computer security book:

When a clerk at University Medical Center, Jacksonville, went into work last Sunday, she took along her 13-year-old daughter, Tammy. Taking advantage of poor computer security, Tammy obtained a two-page report listing former emergency room patients and their phone numbers. She then proceeded to call people on the list and tell them that they had tested HIV positive. Appearing in court this week in handcuffs and leg shackles, Tammy was ordered into state custody. The judge justified harsh measures in this case because Tammy "seemed unconcerned about her arrest or the possible effects of her actions." — Orlando Sentinel, March, 1995

Anyone who remembers the extremely high levels of fear and stigma surrounding HIV back then will know how much damage to individual lives a security and privacy breach like that could cause (there were cases of people taking their own lives upon learning that they had AIDS—although I'm not aware of any suicides resulting from this particular incident).

I'm also unaware of the exact nature of the poor security behind that particular security incident—maybe a workstation had a weak password or was left unlocked while unattended—but it was an early warning of things to come at the intersection of health information and technology.

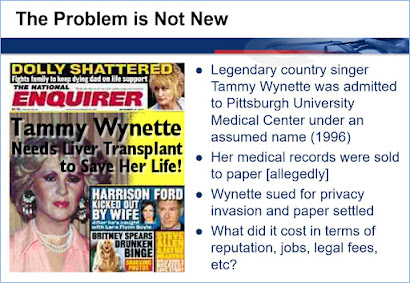

Another warning sign made headlines in 1995: a trashy newspaper paid an employee of UPMC Presbyterian Hospital in Pittsburgh for stolen copies of computerized medical records pertaining to country music legend the Tammy Wynette.

The singer's alleged condition made for a shocking headline, one for which she claimed damages in a lawsuit against the publisher that cited, among other harms, cancelled bookings. Details of the settlement of that suit were never made public, and sleazy papers like that have slush funds for such contingencies, but I would argue that the case raised the security stakes for medical institutions. You can be sure that the hospital took hits to its reputation at multiple stages, from the day the incident came to light, to the coverage of Wynette's lawsuit, then the criminal investigation, prosecution, and conviction of the hospital employee. Along the way it became clear that UPMC Presbyterian‘s authentication systems, password hygiene, and security awareness were all woefully inadequate.

HIPAA hooray?

Bear in mind that both of those cases occurred before America had HIPAA, the one "privacy law" of which just about every American has heard (although most don't know that the "P" in HIPAA doesn't stand for Privacy—see the section headed Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in Chapter 4 of

my free privacy hook, or page 5 of my white paper,

Data privacy and data protection: US law and legislation).

In a nutshell, the purpose of HIPAA was to improve employment-based health insurance coverage. However:

commercial interests—notably insurance companies—claimed that this would be too costly, so provisions to promote the adoption of cost-saving electronic transactions by the healthcare industry were added. Given that such adoption would greatly expand the computerized processing of personal health information, legislators mandated protections for this data in HIPAA.

Although legislators decreed that there should be rules about the privacy and security of health data in HIPAA, they declined to spell them out in the law that they passed. Indeed, legislators dithered on this for several years after the law was passed. Eventually the task of making and enforcing such rules fell to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

The HIPAA Privacy Rule was first proposed in November of 1999, then enacted in December of 2000. It was not until April of 2003 that HIPAA covered entities were required to be in compliance with the Privacy Rule. In conjunction with the Privacy Rule there was also a Security Rule. This was first proposed in August of 1998, and got enacted. in February of 2003, with compliance mandated by April of 2006.

By that time, I had written many thousands of words about HIPAA and delivered dozens of seminars about cybersecurity to healthcare professionals. The image of Tammy Wynette shown above is from a slide deck that I used in those seminars, and in an online privacy training program that I developed.

Note that even then, circa 2000, I was saying "this is not new." What is new in the world of health-related information protection today is the threat level, which has never been higher than it is right now.

This is because criminals have spent a lot of time over the last 20 years devising different ways, to "monetize" the compromising of medical data and systems. At the same time more of this data than ever before is being stored electronically, in one or more types of Electronic Health Record (EHR), held and processed in many different places.

To help raise awareness of this, in 2015 I printed up a bunch of reference cards titled "Electronic Health Records for Criminals" (shown on the right). I started to hand these out to people at healthcare IT events. The size of a postcard, this infographic encapsulates some of the many ways in which the different types of data handled by medical organizations can be abused by criminals.

By the time I gave my talk titled "Cybercrime Triage: Managing Health IT Security Risk" at the massive annual conference of the Health Information Management System Society (HIMSS) in 2016, it was standing room only. (I'm pretty sure the event was larger than RSA that year—with 40,000 attendees and an exhibit space bigger than 20 football fields).

I should note that by the beginning of 2016 the federal government had forced hospitals and other medical organizations to pay out tens of millions of dollars to settle HIPAA cases, brought in large part because these entities had failed to get their cybersecurity act together (despite more than a decade of fair warning).

Trying timing

So why, you might ask, was the medical community so slow to get a grip on cybersecurity? In the US, a lot of can be explained by the government incentivizing, and IT companies enabling, the rapid computerization of health records at scale, without factoring in:

- the well-documented tendency of humans to exploit opportunities for crime

- the perennial reluctance of organizations to invest in computer security

- the historic failure of governments to deter cybercrime

- the healthcare sector's historic lack of exposure to, and experience with IT

On top of all that—or perhaps underlying it if you are a healthcare professional—is a phenomenon that can be summarized in statements like this, which have become part of my cybersecurity awareness talks:

"Doctors and nurses get up and go to work every day to help people. Some criminals get up every day to abuse data, and they don't care how that might hurt people, as long as they can make money doing it."

That reality can be hard to grasp and we might not want to accept it. But it is our current reality here on Planet Earth. If you are in any doubt, fast forward to September, 2020, which brought this headline: "Woman dies during a ransomware attack on a German hospital."

Apparently, "the hospital couldn’t accept emergency patients because of the attack, and the woman was sent to a health care facility around 20 miles away" (The Verge). German prosecutors "believe the woman died from delayed treatment after hackers attacked a hospital’s computers" (The New York Times). What makes this troubling incident all the more emblematic of cybercrime is the fact that it took place during a global pandemic, and the hospital was not the intended target but a case of collateral damage.

Unfortunately, at this point in time, there is a limit to what you and I can do in terms of immediate action to protect our health data from abuse.

Of course, we should all be doing all of the things that everyone's been talking about during this Cybersecurity Awareness Month, from locking down our login and limiting access to all of our connected electronic devices, to being careful how and where we reveal sensitive personal information.

But in my opinion, the heavy lifting in cybersecurity for healthcare has to be done by governments. Firstly, by taking seriously the need to achieve global consensus that health data is off limits to criminals. Secondly, by funding efforts to enforce that consensus at levels many times greater than the paltry sums that have been allocated so far.

Of course, we can all play our part in making these things happen. We can tell our elected representatives that we want these steps to be taken, and that we care about deeply about solving this set of problems. And whenever we vote to elect representatives, we can vote for those most likely to take all this as seriously as it needs to be taken.

Do your part. #BeCyberSmart. Vote!

No comments:

Post a Comment